|

It was the year of 1805, the

year when it seemed that at long last Napoleon would invade England,

which, for twelve years, had stood in the path of the Grand Armée´s

complete domination of Europe. It was the year when, in the face

of all the evidence to the contrary, Napoleon had suddenly convinced

himself that his united fleet could annihilate any squadron which

the English could put to sea to meet it.

In August

of 1805, he wrote to his admirals: „Come into the Channel.

Bring our united fleet and England is ours. If you are only here

for 24 hours, all will be over, and six centuries of shame and

insult will be avenged." In August

of 1805, he wrote to his admirals: „Come into the Channel.

Bring our united fleet and England is ours. If you are only here

for 24 hours, all will be over, and six centuries of shame and

insult will be avenged."

It was an order, however, which his captains found impossible

to obey. Although Napoleon had 2,000 ships and 90,000 men assembled

along the coast of France, the British blockade of the French

and Spanish harbours had virtually ammobilised this gigantic

force.

In desperation, Napoleon ordered his fleet at Cadiz to sail out

and meet the enemy ships which sat quietly waiting on the green

Atlantic swells at Cape Trafalgar, some 80 kilometres east of

Cadiz.

„His Majesty counts for nothing the loss of his ships,"

Napoleon´s message ended, „provided they are lost

with glory."

In response to this order, a Franco-Spanish fleet of 33, with

2,640 guns, commanded by Admiral Villeneuve, set out from Cadiz

to engage the enemy. Massive though this force was compared to

the force that awaited them, its destruction was an almost foregone

conclusion from the very beginning.

There were several reasons for the inevitable destruction of

the Franco-Spanish fleet, not the least being that it was commanded

by a man who was haunted by the memory of his humiliating defeat

at the hands of a much smaller English force only three months

earlier. A man, moreover, that even Napoleon had decided at the

last moment was ill-fitted for the task that had been entrusted

to him.

As Villeneuve was sailing out of Cadiz, a horseman was hastening

down the Spanish Peninsula, carrying a message, informing Villeneuve

that he was to hand over his command to Admiral Rosily.

It would be wrong to assume that if the messenger had arrived

in time to stop Villeneuve sailing, and the highly capable Admiral

Rosily had been in command, the outcome of the Battle of Trafalgar

might have been a different one. There were too many other factors

weighed in the balance against the Franco-Spanish fleet for this

to have happened.

Like Villeneuve, the captains of the Freench and Spanish fleets

were imbued with a sense of impending defeat before they had

even encoutered the enemy. And with good cause!

Demoralised by a long period of inactivity, and with 1,700 sick

men aboard their ships, the French sailed out of Cadiz knowing

that only a miracle could give them a victory.

Press-ganged crews

The Spanish ships, manned mostly

by soldiers or by beggars press-ganged from the slums of Cadiz,

with gunners who had never fired a gun from a rolling ship, and

commanded by Spanish captains who resented being placed under

a French admiral, were in an even worse plight.

Most unnerving of all for the captains of the fleet was the knowledge

that they were about to put themselves against the most skilful

sea captain of all time - Horatio Viscount Nelson.

Only slightly less awe-inspiring was the British Jack Tar himself,

that clay-piped, pig-tailed sailor, who, more often than not,

had been recruited by the press gangs from the scourings of the

English sea towns. Already an aggressive fighting man by instinct,

he had literally been whipped into becoming a magnificent sailor

by the iron discipline of autocratic captains for whom the lash

was the answer to almost every infringement of the ship´s

rules.

A seasoned French sailor would have had difficulty in holding

his own against such a formidable foe, let alone those pathetic

crews sailing out to meet the English fleet.

On the 20th of October, 1805, the Franco-Spanish fleet was sighted,

and soon afterwards the area where the British ships waited became

bright with patches of gaudy bunting as each ship broke out strings

of flags which assed on the message: „The French and Spanish

are out at last, they outnumber us in ships and guns and men:

we are on the eve of the greatest sea fight in history."

On board the flagship, HMS Victory, the message had been delivered

to the English commander, a slight, one-armed man, blind in one

eye and shabbily dressed in a threadbare frock coat stained with

sea salt, its gold lace tarnished to black flattened rags.

Battle plans

This slatternly-looking admiral

was, of course, Lord Nelson, who received the news with the utmost

calmness. And why not? His battle plans had already been made

and communicated to all his captains. Those plans, he was convinced

would give him a swift victory.

Until the Battle of Trafalgar, the problem of how a fleet could

gain an annihilating victory over the enemy was one that had

never really been solved, and for want of a better tactic, it

had been the custom for the fleets to sail into action in two

parallel lines, with each ship taking on a single opponent, firing

its guns broadside as it passed.

Inevitably, the enemy would také an opposite tack, and

the battle would then become a vastly prolonged affair, with

the ships continually sailing on opposite tacks, or engaging

on the same tack, until one of the fleets eventually retired.

Nelson had decided to break completely with this tradition. His

plan was to divide his fleet into two groups. One group would

attack sections of the enemy line and destroy them before other

ships could come to their aid. The other group would attack the

enemy at right angles, break through their lines and then cut

off the retreat of the enemy fleet.

This aggressive piece of strategy, which was later referred to

as the „Nelson Touch", was to change the whole course

of naval warfare.

The battle did not begin until the following day, by which time

the enemy fleet was well in sight, off Cape Trafalgar. Nelson

was on deck, now in a freshly laundered uniform and with new

ribbons for all the medals on his breast.

Battle signal

Shortly after, Nelson called

for the signal officer. „Make the signal to bear down on

the enemy in two lines," he ordered. He then went down to

make his will, which was witnesssed by Captain Hardy and Captain

Blackwood who had come aboard from the Euryalus. Afterwards,

Nelson went up to the poop and ordered that signal officer to

hoist his celebrated signal: ENGLAND EXPECTS THAT EVERY MAN WILL

DO HIS DUTY.

It has been said that this famous signal was to have been worded:

„Nelson confides that every man will do his duty,"

and that his name was replaced by that of England at the suggestion

of the signal officer, who pointed out that if the words „confides

that" were used, they would have to be spelt out with a

long string of flags. The word „expects" was substituted.

First blood

The first shot was fired at the

English ship Royal Sovereign at noon. This salute of iron was

received in silence by the Royal Sovereign, who waited until

she had drawn astern of the Spanish three-decket, Santa Anna,

then raked her decks with a murderous fire that killed or wounded

400 of her crew.

In the meantime, Nelson´s ship was moving on, silent and

intent, searching for the French admiral´s ship. Eventually,

right in front of her, lay the huge Spanish four-decker, Santissima

Trinidad. Guessing correctly that the French admiral´s

ship must be nearby, Nelson bore down on her. As he did so, the

Bucentaure, Villeneuve´s ship, and seven or eight other

enemy ships, opened fire on the Victory. Still she advanced without

firing. By the time she had come close enough to rake the Santissima

Trinidad with her larboard guns, 50 of her men were dead and

30 wounded.

It was at this point that the Victory came into collision with

the French Redoubtable. Locked together, and wrapped in sheets

of flame, the two ships drifted slowly through the smoke of battle.

Gradually, although the fighting had continued unabated, the

smoke cleared a little from the decks of the Victory, enough

for the marksmen to see the epaulets of the English officers.

A marksman kneeling in the mizzen-top aimed his musket at Nelson.

On the quarterdeck of the Victory, Captain Hardy had turned to

leave Nelson´s side to give an order when Nelson fell,

mortally wounded. Immediately, Hardy, a sergeant of the marines

and two privates, rushed forward to lift him up. Nelson was then

carried down to the cockpit, where he ordered that his face should

be covered with a handkerchief so that he might not be recognized.

In the meantime, the Redoubtable´s top marksmen had shot

down 40 officers and men, destroying so many that the French,

seeing the upper deck clear of all but dead or wounded, tried

to board her. It was an enterprise which was to cost them dear.

A botswain´s whistle piped, „Boarders; repel Boarders",

and the order immediately summoned swarms of smoke-begrimed blue-jackets

to the deck, where they killed every man who had managed to board

the Victory.

Below decks, Nelson´s life was now ebbing away fast. But

he was still alive when Hardy returned from the fighting above

to inform him that fourteen enemy vessels had given in. „That´s

well," Nelson said, „but I had bargained for twenty."

He lingered on for a little while longer. After murmuring some

inarticulate words, he said distinctly, „I have done my

duty. I thank God for it!"

|

|

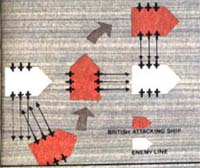

The first stage of the battle, with

the Victory leading a frontal attack, while the rest of Nelson´s

fleet attacks at right angles to break through the lines of the

enemy ships, and thus cut off their retreat. This tactic was

in complete variance with all the accepted rules of naval warfare. |

|

The

last stage of the battle, with the French and English ships engaged

in a general melée. By then 25 French ships were already

out of action and trying to make for Cadiz. The

last stage of the battle, with the French and English ships engaged

in a general melée. By then 25 French ships were already

out of action and trying to make for Cadiz. |

|

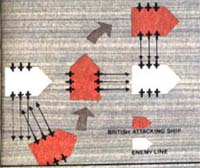

The raking manoeuvre employed with

great success by the British ships. When attacking the enemy

line, a British vessel would steer for a gap between enemy vessels.

After brilliant seamanship had gained the British ship an advantageous

position, a broadside was fired at one enemy vessel before sailing

in front of it to unleash yet another broadside into the stern

of the next ship in the line. Yet another broadside was then

delivered to that crippled vessel from the other side. |

|

Ruined dream

Above,beneath the setting sun,

his fleet was lying in two groups with the shattered hulks of

the enemy ships all around them. The British losses had been

heavy; 449 killed and 1,241 wounded. But of the 27 ships of the

British fleet, not one had been sunk or captured. Trafalgar was

the decisive battle of the Napoleonic Wars.

It had always been essential to Napoleon´s master plan

to control the world that he should have command of the seas.

With his Allied fleet now ruined as a fighting force thet dream

had been destroyed forever.

Trafalgar, moreover, established England´s supremacy at

sea for nearly a century and a half, during which time her navy

remained the bedrock on which her control of the far-flung British

Empire rested through the age of steam and into the 20th century. |

In August

of 1805, he wrote to his admirals: „Come into the Channel.

Bring our united fleet and England is ours. If you are only here

for 24 hours, all will be over, and six centuries of shame and

insult will be avenged."

In August

of 1805, he wrote to his admirals: „Come into the Channel.

Bring our united fleet and England is ours. If you are only here

for 24 hours, all will be over, and six centuries of shame and

insult will be avenged."

The

last stage of the battle, with the French and English ships engaged

in a general melée. By then 25 French ships were already

out of action and trying to make for Cadiz.

The

last stage of the battle, with the French and English ships engaged

in a general melée. By then 25 French ships were already

out of action and trying to make for Cadiz.